Salute

Anti-aids vaccine: illusion or reality?

Montaigner is developing a vaccine to stop Hiv from being transmitted from mother to child. Like him, many others are working to find an anti-Aids vaccine, with few funds and little support.

di Staff

Nobel peace prize laureate Luc Montagnier announces that: “We are working to develop a vaccine for children”. The well known doctor and professor, who, together with Robert Gallo, discovered the virus that causes Aids 25 years ago, is working in the African continent to achieve a dream: to develop a vaccine that would prevent Aids from being transmitted to children.

The field work is being carried out by a group of Italian and American researchers and coordinated by Vittorio Colizzi, a professor from the University Tor Vergata in Rome and one of Europe’s greatest Aids experts. “We are studying the vaccine in three countries: Burkina Faso, the Ivory Coast and Cameroon”, explains the professor over the phone from Yaoundé, Cameroon’s capital city. “The vaccine will be administered along with the antituberculous vaccine, Bcg, that is given to newborn babies in Africa. It will be administered on the first day of birth to prevent the Hiv virus from spreading from mother to child”.

An open frontier

Research into a children’s vaccine is one of the struggle against Aids’ open frontiers. “Unfortunately it is still not a much explored option,” says Colizzi, who adds that: “There are very few experiments underway at the moment and few funds, most of them public.” When it comes to expressing an opinion about the results so far, the professor is cautious: “Expectations can lead to cold showers when you are working to develop a vaccine. Now the important thing is to keep at it.”

Vaccines take a long time to develop, in the case of Hiv the time frame is even longer. The programme directed by the Italian virologist – which includes training African doctors, transferring technologies and the equipment to three centres in Africa where the vaccine will be tested – began in 2003, with Unesco’s support and with a 2 million euro contribution from the Italian government. Then the project was endorsed by Gallo and Montaigner three years ago. Five years later the vaccine is being produced industrially. “Once the compound is ready the clinical trials will begin, these are scheduled for the end of 2009,” expalins Colizzi. So even if the vaccine is successful it will take many years before it will be available. December 1st is World Aids Day and the scientific community is frustrated. Research into vaccines to prevent Hiv virus is compared by some to a Sisyphean enterprise: “Every time we think we have carried the rock to the top of the mountain we realize that it has already started rolling down again”, writes Jens Lundgren, director of Copenhagen’s Programme for research into Hiv. There are about 30 anti- Aids vaccines being tested in the world today: The most advanced vaccine, Merck’s vaccine, proved to be ineffective, explains Giuliano Rizzardini, director of the unit for contagious diseases at Milan’s Sacco hospital. In the eighties Rizzardini cured one of the first Italian cases of infection, Lucille Corti, who contracted Hiv while operating on a patient in Uganda. “At the time there was only one medicine, called Azt, to fight Aids. Now, on the other hand, doctors can count on several effective medical cocktails”.

But the future looks less bright for vaccines: “So far many of them have proved ineffective, they cannot protect against the virus because of the virus’ inherent characteristic, which is to change shape continuously. At present the idea is to re-evaluate all the research, and to start again from scratch, by studying Hiv’s replication mechanisms.

Timing

”When it comes to anti-Aids vaccines, there are two main problems: the long time frame and difficulty in proving their effectiveness”, says Fabrizio Pregliasco, an expert virologist at Milan University’s public health department and vice-president of Anpas- the Italian national association for welfare assistance. It takes about ten years to produce a vaccine. First there are the laboratory experiments and stages when the vaccine is tested on animals, then the the clinical trials on humans start which, in the case of anti-Aids vaccines, have three consecutive phases. “At an international

level we don’t know what point research is at and there is no effective external monitoring”, continues Pregliasco. The World Health Organization is trying to create an international network, with the Initiative for vaccine research, a programme that aims at coordinating, encouraging and supporting research into anti-Aids vaccines. The initiative was launched in cooperation with the United Nations programme on Hiv/Aids and at present it provides the only shared database of active research.

Business doesn’t believe in Anti-Aids vaccines

Funding is another problem: “Public funds are just enough to keep research going and private funds only come from not for profit foundations like the Bill and Melinda Gates foundation”, explains Pregliasco. “Pharmaceutical industry has little interest: the investment risk, that is to say at least ten years, is high, and there is a low profitability in case of success”.

According to researchers like Guido Silvestri of Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania School of Medicine, one of the most esteemed researchers in the United States, “we have reached a ceiling in the struggle against the disease, for this reason it’s essential to find alternative routes”.

According to professor Colizzi, research into a children’s vaccine is easier and could provide useful information for the development of other anti-Aids vaccines. Over the course of the last few years a medicine called nevirapine has been used to block the virus’ transmission from mother to child. “The children’s vaccine is the solution all of us are waiting for”, says Roberto Moretti, who is medical and sanitary consultant for Bergamo’s Cesvi. Cesvi has been among the first organizations to introduce and distribute nevirapine in Zimbabwe and has been doing so since 2001. ” Many more mothers could be reached in a simple and effective way with the vaccine. But for the time being it remains just a hypothesis”.

Translation by: Cristina Barbetta

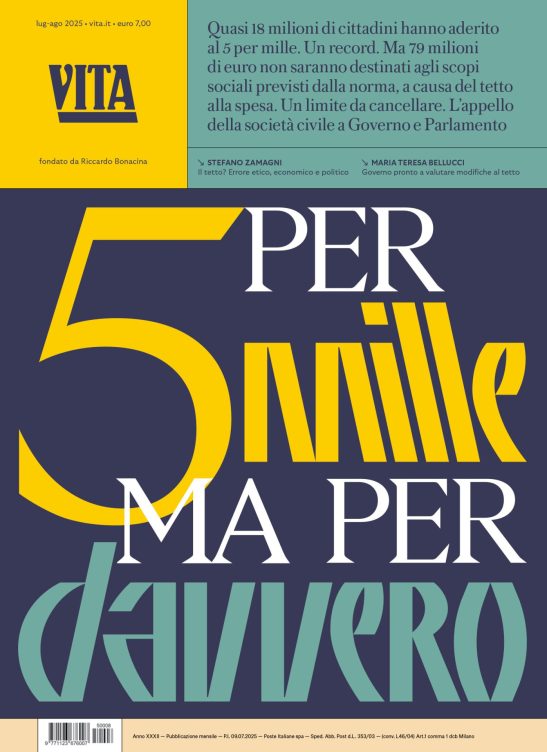

Nessuno ti regala niente, noi sì

Hai letto questo articolo liberamente, senza essere bloccato dopo le prime righe. Ti è piaciuto? L’hai trovato interessante e utile? Gli articoli online di VITA sono in larga parte accessibili gratuitamente. Ci teniamo sia così per sempre, perché l’informazione è un diritto di tutti. E possiamo farlo grazie al supporto di chi si abbona.