Zimbabwe’s activists call on Brussels for human rights

Ballots will be replaced by bullets in Zimbabwe's national elections on June 27 unless the international community steps in, say activists

di Redazione

Zimbabwean activists call on the international community to protect the people of Zimbabwe in the run up to the scheduled June 27 elections. “Ballots will be replaced by bullets unless the international community acts immediately” said the Ecumenical Zimbabwe Network, a network of over 53 faith-based and humanitarian organisations, this week in a press release in Brussels.

Vita Europe met with Steve Kibble, advocacy coordinator for international development charity Progressio to find out what the situation is and why European civil society has not responded to the Zimbabwean call.

The crisis in Zimbabwe has been going on for a long time but there has not been much mobilisation by part of European civil society, especially in Italy. Why do you think this is?

I think that countries like Denmark, Germany Belgium, the UK and Ireland, which are all countries that were involved in Zimbabwe’s liberation struggle in the 1980’s and 1990’s have actually been quite active in civil society networks recently. There certainly has been a difference in the reaction to the crisis between northern European and southern European NGOs and I think that this difference is down to how civil society is set up in the different countries. However there has been some civil society interest from Spain, perhaps because of its geographical position.So yes, I think that certainly there has been a lack of interest from Italy and other Eastern European countries and that perhaps the reasons can be found in the historical traditions of the civil societies of these countries.

According to reports the violence in Zimbabwe is still going on …

Oh yes, the violence continues. People are calling it ‘electoral cleansing’: the state is still keen to displace voters who they suspect may be voting for the opposition, taking their electoral cards away from them, beating them up, subjecting them to horrific injury and generally ensuring that the climate of fear and intimidation makes it impossible for free and fair election.

There has been some indication that the people in charge of this strategy of terror are beginning to relax and call in their militias, as though they think that this will make people think that there is the possibility of a free and fair election, even though this is hardly plausible with only one candidate. But I think that it is a cosmetic move as there is no sign that the subtle violence and intimidation won’t continue but that maybe some of the overt violence and intimidation has served its purpose. This, however depends what you think the purpose of it was.

What do you mean?

In my estimation the election was only part and parcel of a wider battle for what kind of Zimbabwe people wanted to see. People tend to dismiss the statements Mugabe makes, but when he says he wants to see his projects of indigenisation, and Zimbabweans controlling all aspects of society I think we have to take him seriously. Even though he is destroying the very economy he hopes to indigenise, he doesn’t necessarily see that as a paradox. So the violence is aimed at creating the Zimbabwe that Robert Mugabe wants, one part of which is the election process.

Other African governments appear to have had a ‘soft’ attitude towards Mugabe. Why do you think there are so few African governments that have directly condemned him?

For a long time criticisms of Mugabe seemed only to come from the West, from the old colonial masters. This apparent ‘harassing’ of African leaders was very negatively received, especially given the charges of Western hypocrisy over Iraq and Afghanistan and Guantanamo Bay. It looked like Westerners had one law for Africa and another for themselves.

I think that Mugabe used this anti colonial rhetoric to suggest that the fight was between Britain and Zimbabwe or the US and Zimbabwe and that the opposition was not a real political party, that it was a Trojan horse for Western imperial interests. And he was able to do this for quite some time. Of course, he also had his history of being a hero of the liberation struggle, which helped him maintain support in Africa and other parts of the developing world. It is only recently that the opposition, the Movement for Democratic Change, and some of the international groups we work with were able to show that this is not a crisis about anti colonialism but that this is a crisis about governance, about legitimacy, about oppression.

Has this translated into any concrete actions?

We are beginning to see that African leaders are speaking out, that the African Union, for example, in 2005 delivered, through its Commission on human and peoples rights, a very damming report on human rights abuses in Zimbabwe; the UN Special Representative, who is Tanzanian, has produced a similar report; there are voices in the Southern African Development Community (Sadic), that make open public criticisms.

President dos Santos of Angola, although by no means a democrat (he is also facing elections this year, which may explain his motives) has called on Mugabe to obey the rule of law and fair elections. Church leaders have done the same and retired African leaders signed a big statement the other day calling the conditions for a free and fair election and for democratisation and an end to the abuse of human rights. The United Nations Security Council, for the first time ever, issued a statement unanimously denouncing the violence and calling for a new electoral process.

All of this suggests that African leaders have begun to move and to realise what the nature of the crisis is: an internal crisis of governance.

Where will they go from here?

This is a mute point, because while it is fine to decry the violence, are they really prepared to operate the general assembly of the United Nations resolution that says it is the duty of governments to protect their citizens and if not, other governments can step in and do it for them. When Desmond Tutu called for a Peace keeping force many people raised their eyebrows, but now they are beginning to see it may be one way out of the crisis: that African neighbouring states and the African Union can put significant pressure on Mugabe to either step down or stop the violence and look to create a more peaceful and prosperous Zimbabwe.

In your opinion can churches still speak out in Zimbabwe?

It is difficult for them, but I think that in a sense they have more space than other civil society actors. Also, Mugabe is a Catholic, a very bad one no doubt! But he is aware of church hostility and he is trying to subvert the church to his own ends, hence the campaign against Archbishop Pius Ncube, the previous Archbishop of Bulawayo. The churches themselves have been divided: the Catholics in Zimbabwe were traditionally intertwined with the liberation movement, while the Anglican church was seen as the pillar of the old colonial regime; the Evangelicals were fairly non political. As of the 90’s this began to change, the churches were involved in the national referendum of 2000 which Mugabe lost, and they were a bit scared by what they’d done. The response now has been varied: some religious leaders have spoken out, some have been fearful, some have been bought off with land and inducements, some actually agree with Mugabe anyway. There have always been these divisions. What has changed in this decade is that middle level churches have begun to ask their leaders to speak out, they form groups like the Christian Alliance which has been very outspoken both in theological and political terms about what the nature of the crisis is. There has been the Catholic Bishop’s statements last year, God hears the cries of the oppressed, which for the first time ever named the state as the main perpetrator of violence, as the main source of corruption and repression and basically calling for a new Zimbabwe. The heads of Denomination came out with very strong statements in April this year warning against genocide, which was for many people a real eye opener. So yes, in a sense churches do have a voice and certainly have more space to speak than many other civil society organisations who can’t make such strong statements.

What main challenges does Progressio face at the moment?

Progressio is an organisation that works inside developing countries, including Zimbabwe, which means we have to be mindful of the security side of things. In terms of our networking with groups like the Ecumenical Zimbabwe Network we are keen to provide information, to support fellow organisations North and South, in making plain what the nature of the crisis is and to do something about it. By lobbying, by commenting on draft resolutions in the European parliament, by talking to our various national governments about what has to be done. We also work with the Zimbabwe Human Rights Forum which in turn works with a number of African institutions like the African Commission of human and peoples rights in the African Union. So networking is another of our challenges. Then there is the advocacy and lobbying element to what we do: disseminating information, although we are careful not to mention who we are when speaking out as it is thought to be dangerous, especially as we do carry out operations, like HIV programmes, on the field in Zimbabwe.

Find out more

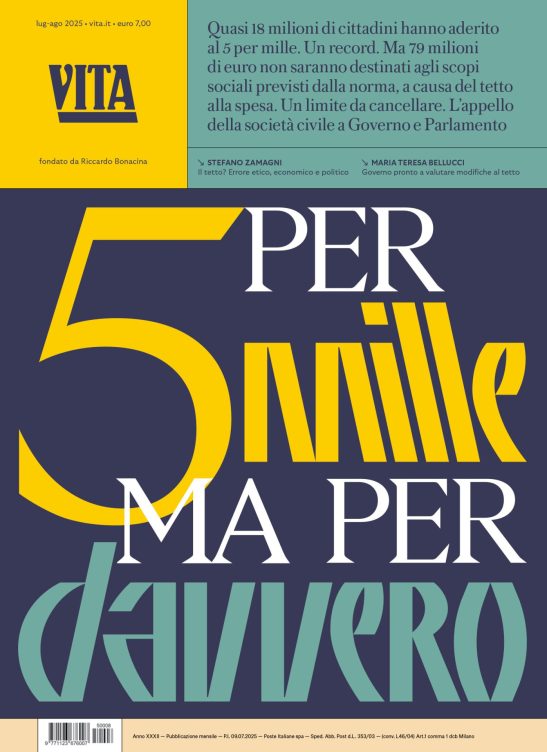

Vuoi accedere all'archivio di VITA?

Con un abbonamento annuale potrai sfogliare più di 50 numeri del nostro magazine, da gennaio 2020 ad oggi: ogni numero una storia sempre attuale. Oltre a tutti i contenuti extra come le newsletter tematiche, i podcast, le infografiche e gli approfondimenti.